Black Woman Savior Trope Toolkit

I Am Not Your Savior

Dismantling the Black Woman Savior Trope

Toolkit Research by Thea Gay

key summary

Positioning Black women as saviors of the world is not a compliment.

Instead, it is a clear indication that Black women have become mythologized by racist ideologies as soldiers, “ready” and “capable” to save the world from itself. Many Black women engage in activist work to liberate themselves from a society that degrades their existence. But they are continually expected to show up even if that means fighting for the interests of others with no one fighting for theirs.

This idea is rooted in the racialization, control, and oppression of Black women to take on the burden of society’s ills without complaint or recognition. It creates a monolithic perception, leaving no room for them to be who they are or want to be. In every social movement including the environmental one, they are consistently told they don’t belong. And yet they are called to save the same world that erases their humanity just so it can continue to operate in the same manner.

In this digital toolkit, we will explore how the intersections between race and gender have historically created multiple forces of oppression against Black women. We will examine the relationship between Black women in the environmental movement and the Black Woman Savior. And lastly, we will provide some collective and individual actions to combat this toxic trope and ultimately ensure the protection and upliftment of Black women.

definitions

Black Woman Savior Trope

noun - the mythologization of Black women as soldiers “ready” and “capable” to save the world from itself. In this trope, Black women’s identity and purpose are simmered down to their servitude for others, despite their capacity, needs, wants, and interests. They are pushed to save the world and take on the burden of society’s ills (and those they personally face) because it is assumed they have the strength to do so. And they’re expected to do it all without complaint or recognition.

Misogynoir

noun - a type of misogyny, or hatred of women, directed specifically at Black women, where both gender and race play a role in their discrimination.

Black Women

noun - Including Black women, femmes, and trans women.

where does this trope come from?

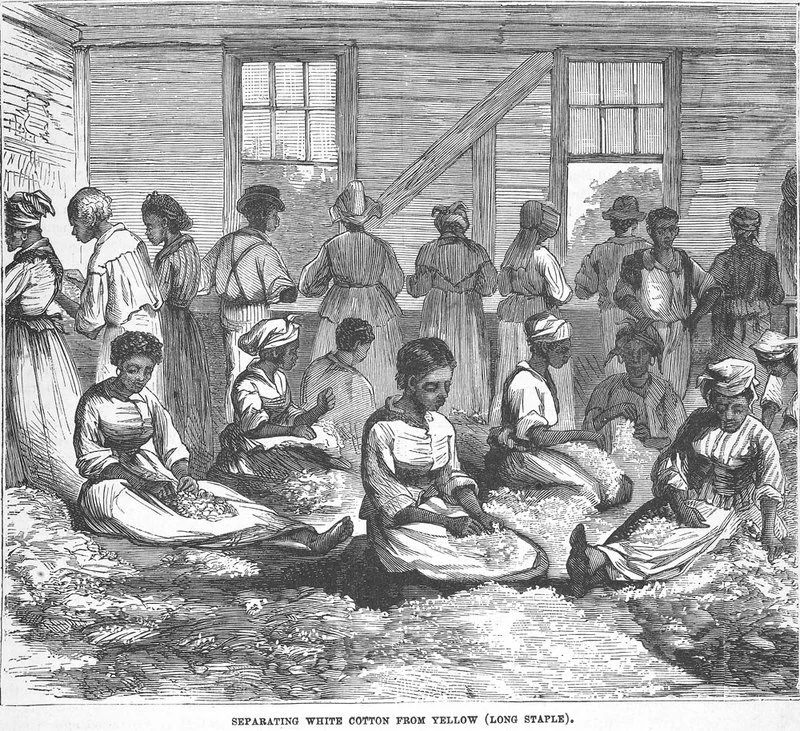

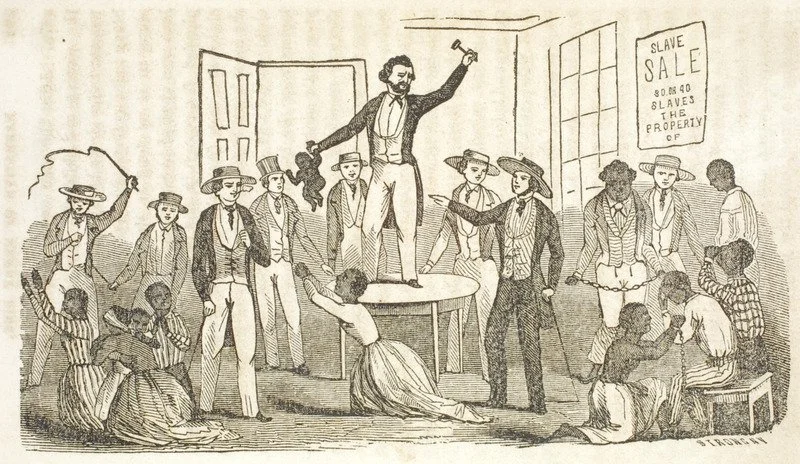

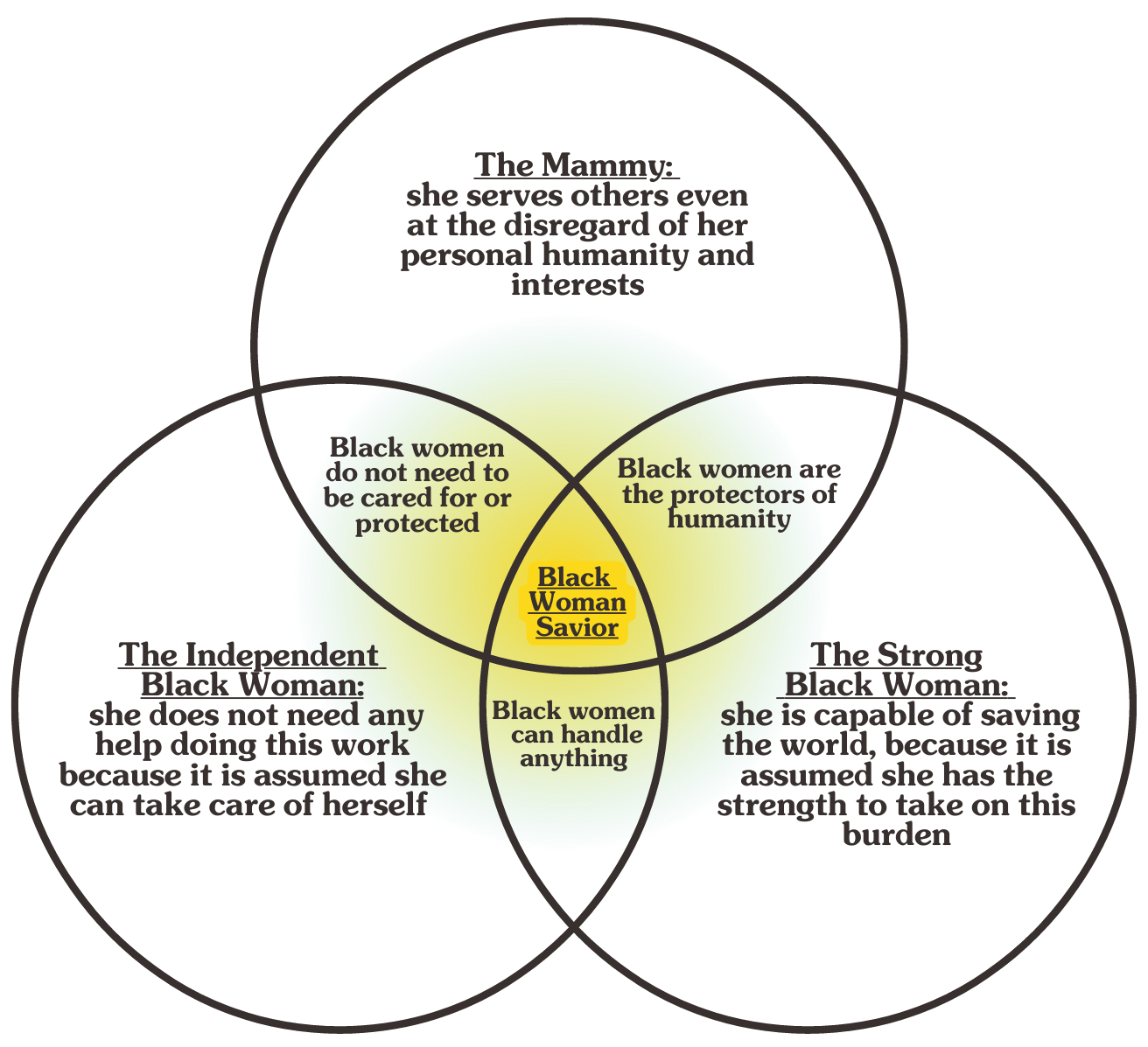

This trope dates back to the period of African enslavement (15th to 19th century), in which Black women were exposed to a society that was violently patriarchal and racist. They were regulated to intense physical fieldwork and traditional domestic labor, often under poor living conditions. Black women had the least amount of power and protection, experiencing physical, emotional, and sexual violence as a result of their intersecting identities. As well as institutionalized economic and gendered exploitation. From the end of slavery to the 20th century to today, there have been a plethora of misogynoir stereotypes specifically targeted at Black women. Specifically, we can hone in on these three stereotypes to better understand the evolution of the Black woman savior trope:

The Mammy: used to represent Black women as undesirable and desexualized beings whose sole purpose is to serve others, especially white families and institutions.

The Strong Black Woman: used to justify the mistreatment, discrimination, and exploitation of Black women because they are strong enough to handle it.

The Independent Black Woman: used to represent Black women as strong and independent, able to individually support themselves and are proud to do so.

Thus leading us to the Black Woman Savior. This trope was specifically meant to tackle the negative ideas associated with the Mammy, the Strong Black Woman, and the Independent Black Woman, but in many ways, it is a combination of the three.

Images: (Left) African American Women Separating White Cotton from Yellow (Long Staple), South Carolina, 1880 (Right) Slave Auction, U.S. South, ca. 1840s

The Black Woman Savior Trope is rooted in the racialization, control, and oppression of Black women to take on the burden of society’s ills without complaint or recognition. It creates a monolithic perception, leaving no room for them to be who they are or want to be.

data chart on the Black Woman Savior

In these narratives, Black women don’t have agency or choice. So much so that at the discretion of powerful groups they can be immediately erased and even silenced when they are not seen as favorable to the cause*. They are attempts to control perceptions around Black women to justify their marginalization as natural and inevitable. These stereotypes dehumanize, silence, and render Black women invisible, positioning them as Black, before human. A life completely centered around race has turned the perception of Black women from a diverse and nuanced group of people into monoliths.

*Ugandan climate activist Vanessa Nakate knows this story all to well when she was cropped out of the AP's photograph featuring four other White activists, essentially erasing her from the movement.

Black Women in the Environmental Movement

There is a long-standing misconception that Black people have no interest for the environment. Mainstream environmentalism is largely associated with Whiteness, despite the fact that these issues are strongly linked to health, social, economic, and racial disparities in Black communities. Starting at the grassroots level in the early 1980s, the Environmental Justice Movement (EJM) began in response to the continued legacy of systemic inequality and environmental discrimination against African Americans. This movement fights for meaningful and inclusive environmental regulations and policies that strengthen public awareness on the disproportionate impact environmental issues (e.g. pollution, climate change, etc.) have on communities of color. It is rooted in Black history and it has been powered and led by Black women since the very beginning.

We can look to icons such as:

These women and many more laid the foundation for today’s generation of EJ activists, as they all have continued fighting for many of the same rights, protections, and liberties 40 years later.

the EJM and The Black Woman Savior

The work of Black women in the environmental movement continues to serve the world in meaningful and abundant ways. But at the same time, their contributions have not been fully recognized or rewarded. Celebrations of Black women as saviors fall short of actually acknowledging and compensating them for the work that they do. Especially as they have been forced to create their own seat at the table because those in power have historically refused to acknowledge their wisdom and leadership. Even still, they must continually prove why their existence and the communities they represent matter.

According to the Status of Black Women in the United States report (2017) from the Institute for Women’s Policy Research and the National Domestic Workers Alliance “Black women’s contributions to U.S. society and the economy have been undervalued and undercompensated.” As a racialized group, Black women are constantly carrying the trauma, labor, and even abuse that comes with fighting for environmental justice and liberation. This impacts their mental, physical, and emotional health, which are often downplayed by society and ultimately left widely untreated. And they do all this while still dealing with their own personal responsibilities.

We cannot continue to treat Black women like expendable resources for the sake of the planet’s survival. We must recognize the full humanity, diversity, and uniqueness of this community. And at all costs, we must protect Black women.

“The mainstream environmental movement must acknowledge the social pressures, standards, and stereotypes that Black women are expected to live up to, as well as the unique burdens and systems of oppression that keep them at the lowest of the social hierarchy yet at the forefront of every battle.”

Thea Gay

conclusion

Here are some action steps necessary to combat the Black Woman Savior trope:

Suggestions for Allies:

Support Black women by listening to them, using your individual power to advocate for them, and/ or investing in their movements and campaigns.

Educate yourself on issues that disproportionately impact Black women and girls. Don’t expect them to do that work for you.

Decolonize yourself by critically analyzing your own biases and assumptions regarding race and gender.

Take the issues Black women face seriously. You may not identify as one, but just like you, they have the right to a life free from racist narratives.

Suggestions for Black Women:

Put yourself and your needs first. You don’t have to prove you are enough because your existence is enough.

Remember rest is resistance. You have a right to rest and feel good. Black Joy is what they don’t want us to have, so take it all for yourself!

Draw boundaries and be aware of what you can and cannot handle, you are not the only one needed to do this type of work.

Urge that anyone seeking to be an ally of Black women undoubtedly and truly work with us in our fight for liberation.

Realize that activist work is a choice, not an inherent duty you have to partake in.

Collective Suggestions:

Hold society accountable for doing right by Black women and ensuring they are able to reap the fruits of their labor.

Reject cultural stereotypes and narratives that dehumanize Black women and erase the unique issues they face.

Actively adopt an intersectional view on environmental, social, racial, and economic justice because they are all interconnected.

resources

Organizations

Black Women’s Health Imperative

Black Women's Health Imperative is the oldest national organization dedicated solely to improving the health and wellness of our nation’s 21 million Black women and girls – physically, emotionally and financially.

The National Black Women's Justice Institute

The National Black Women’s Justice Institute (NBWJI) aims to eliminate racial and gender disparities in the U.S. criminal-legal system that are responsible for its disproportionate impact on Black women, girls, and gender-expansive people.

Black Women’s Blueprint (BWB) was founded in 2008 by survivors for survivors committed to healing and transformation. Their mission is to provide services and spaces for healing, reconciliation, and human connection with the natural world.

Youtube

Books

Podcasts

Further Reading

about the researcher

Thea E. Gay is a Spring Programming Fellow at IE.

She is currently getting her B.A. in Sociology with a passion for racial, social, and environmental justice!

IG: @organicallythea

Linkedin: Thea Gay

References

Clarke, S. (2021). The Black Eco List: Black women making environmental history now. Meet The Black Women Making Environmental History. Retrieved from https://www.refinery29.com/en-us/2021/04/10403951/black-eco-list-women-environmentalists-earth-day

DuMonthier, A., Childers, C., & Milli, J. (2017). Introduction. In *The Status of Black Women: in the United States* (pp. xiv–xxi). Institute for Women’s Policy Research. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep27082.4

Jones, R. (2021). The environmental movement is very white. these leaders want to change that. History. Retrieved from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/environmental-movement-very-white-these-leaders-want-change-that

Moody, Mia (2011). ["A rhetorical analysis of the meaning of the 'independent woman"](http://ac-journal.org/journal/pubs/2011/spring/Moody-Ramirez.pdf) (PDF). *American Communication Journal

Oladipo, G. (2021). As black women, we need to save ourselves, not the world. Healthline. From https://www.healthline.com/health/black-women-need-to-save-ourselves#Where-do-we-go-from-here?

Saxton (2003) Being Good: Women's Moral Values in Early America: New York: Hill and Wang 388 pg 124,

Willis, S. (2020). Black women are leading the way in environmental justice. Essence. Retrieved from https://www.essence.com/news/black-women-are-leading-the-way-in-environmental-justice/